topic

jurisdiction

downloadable assets

article

Sample

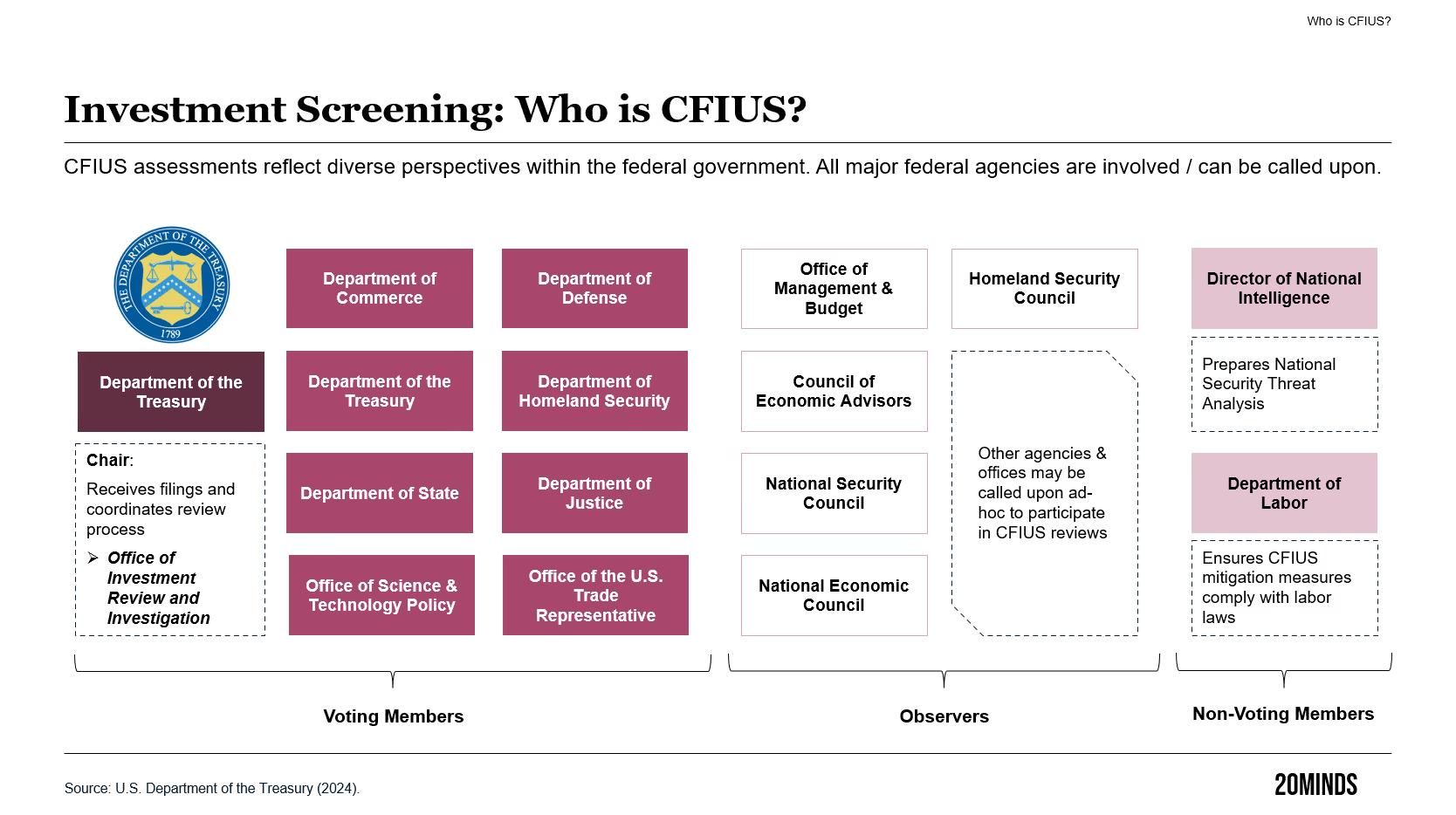

Global investors are very mindful, if not fearful, of the ability of CFIUS to intervene in their transactions. What makes CFIUS such a powerful regulator?

Rod: CFIUS supports the president when deciding whether to block or suspend foreign investments into US businesses that he deems to present national security risks.

CFIUS administers a "Mother May I" approach that affords the Committee broad discretion.

In countries with the rule of law, regulators normally must prescribe a rule before taking action. For example, the US Commerce Department must classify technology before it may control its export.

By contrast, CFIUS waits for parties to present a transaction. CFIUS staff then have free rein in asking questions, which need not be limited to the four corners of the particular transaction.

Where CFIUS officials identify security concerns, they may insist on mitigation as a condition of clearance. CFIUS officials need provide only the most superficial of explanations and parties have no effective ability to question the merit of the officials' reasoning.

How CFIUS evaluates transactions

CFIUS screens foreign investments into US businesses for risks to US national security. Is there a specific methodology that CFIUS applies?

Rod: CFIUS uses a "threat + vulnerabilities = risk" framework to analyze transactions. It assesses whether an investor presents a threat that, when combined with national security vulnerabilities presented by the target US business, creates national security risks to be mitigated.

Let's unpack this: What are the national security vulnerabilities that CFIUS is concerned about, and who poses a threat from the perspective of CFIUS?

Rod: Vulnerabilities presented by the US target business typically fall into four categories. Much of the analytical work in CFIUS cases focuses on these vulnerabilities:

- Technology transfer (especially technology and know-how not classified for export controls);

- Security of supply (usually for the Defense Department, this being the original CFIUS concern);

- Espionage (mostly data, also media); and

- Disruption (mostly infrastructure and IT systems).

On the threat side, CFIUS assumes investors from China present a threat on the basis that the Chinese government could oblige even private Chinese entities to do its bidding.

CFIUS also scrutinizes investments from other countries, particularly where the investor is affiliates with a state.

CFIUS during the Biden administration has sought to impose "precautionary" mitigation where foreign firms from other countries, even highly regarded entities from allied countries, invest in US businesses.

The Committee implemented its "precautionary policy" in response to concerns that US national security may be impaired not only by Chinese entities directly investing in sensitive US businesses, but also by investments from non-Chinese investors who have significant exposure to the Chinese market.

CFIUS members have grown increasingly concerned about those "third-party" risks arising from investors' China exposure.

The result has been a proliferation of mitigation measures, often in the form of National Security Agreements (NSAs),1 with more than one in five CFIUS notices now leading to an NSA.

What role is CFIUS playing in fostering economic disintegration of the US and Chinese economies?

Rod: CFIUS has screened many China-US transactions, of which several have been blocked by the President on the recommendation of CFIUS or have been abandoned by the parties. Others have been cleared subject to mitigation. The Chinese government may have "retaliated" on some occasions, although not openly. Of course, the Chinese market has never been entirely open. The increasingly challenging Sino-US relations are shrinking the space available for private parties to transact business in the other jurisdiction.

But CFIUS’s impact goes beyond halting investments and unwinding foreign ownership structures.

By screening hundreds of foreign investments each year, CFIUS has become a “policy lab” for regulations targeting threats of espionage and disruption of sensitive IT systems.

Not only do CFIUS cases allow officials to study risks arising from economic integration, but CFIUS officials can also trial potential regulations to remedy the situation. The bespoke “regulations” are the NSAs that the parties must enter into to secure CFIUS clearance.

Implementing numerous NSAs over the past five years and monitoring compliance have given CFIUS agencies a much more sophisticated understanding of data flows and vulnerabilities embedded in hardware and software than the government would have otherwise had. Equipped with these insights, agencies are now working to address vulnerabilities directly, i.e., outside the context of a transaction.

Looking at the potential effect of these policies, are we still talking about de-risking or already decoupling?

Rod: “Decoupling piecemeal” would be an appropriate description of what we have been observing over the last two presidential terms.

Both President Trump and President Biden have used the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA)2 to create, without involvement of Congress, entirely new regulatory programs of potentially broad sweep against Chinese economic influence in the US.

While these national security measures focused on espionage and disruption vulnerabilities, they could sever swaths of Sino-US economic integration. The long-term consequence will be increasing economic segregation, at least in tech and data sectors.

Consequences will not be immediate. They will play out over years. The regulations will not attract the headlines of tariffs or semiconductor controls. They will unwind integration incrementally. Regulators implement new regulations, sector by sector. Each time, they will bring about consequential impacts on market opportunities for businesses whose plans depend on integrated markets. Some may call it “de-risking,” but it is going to feel a lot like decoupling for the individual firms.

Which of these policies are going to have the largest impact?

Rod: Impacts will be most significant in the IT sector where China's manufacturing presence is dominant.

At the end of his first term, President Trump issued an executive order directing the Commerce Secretary to promulgate regulations on information and communications technology and services. President Biden's Commerce Secretary issued the regulations and erected an office to implement the new rules.

The first China-connected products restricted under these new regulations are connected vehicles, which is just about any vehicle today.

I doubt that it will stop here. In the Internet of Things (IoT) era, virtually all appliances and equipment with a China nexus could eventually fall within the reach of similar restrictions – not just electric vehicles and vehicle components, but also cranes, industrial equipment, smartphones, and even household appliances.

Further, restrictions will likely not be limited to hardware and equipment but may reach software and IT services, including where Chinese software developers support a US company's app, website, etc.

What about data-intensive industries, like social media, health apps, or ad-tech?

Rod: Data is another target of US rulemaking. Last year, President Biden issued a “groundbreaking” Data Security Executive Order, and the Justice Department has now promulgated regulations that will prohibit data transactions affording access to US personal data to Chinese entities.

The rules resemble restrictions seen in NSAs imposed by CFIUS on individual Chinese firms with access to US personal data.

While framed in terms of regulating transfers of US citizen data to Chinese entities, virtually all US businesses handling significant volumes of data may find it necessary to comply with the data security requirements, even if they are not aware of specific interactions with Chinese entities.

This is also relevant for the health sector, which typically deals with large amounts of sensitive data. The BIOSECURE Act, which aims to protect US biotech supply chains from foreign adversaries, has the potential to severely restrict the ability of US biopharmaceutical companies to collaborate with certain Chinese entities without losing the ability to contract with the US government.

My company is neither from the US nor China. Am I still going to be impacted?

Rod: Likely yes. There are two forces at play here:

First, the US government will try to persuade its allies, in particular the EU, the UK, Japan, and South Korea, to adopt similar rules. It has done so successfully with foreign investment screening and export control regulations. If successful, companies in these countries will also find it harder to rely on Chinese suppliers.

Second, all companies with a significant US business may end up implementing US data security rules to simplify compliance. We saw this with the EU GDPR a few years ago in the area of data protection and called this “the Brussels effect”. For data security, we may now observe a “DC effect,” with the result of increasing data localization. If you are operating in the US, EU and Chinese markets, you don't want to have different standards within your group; you submit to the higher standard. So these companies, for efficiency reasons, may impose the same US data security standards across their group, although they may technically not obligated to do so group-wide.

Rod Hunter, a partner based in the Washington, DC office of Baker McKenzie, practices trade and investment law. He previously served as Special Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs and senior director for international economics at the National Security Council (NSC), the White House office that coordinates trade policy and supervises CFIUS.

Sources

- National Security Agreements (NSAs) are legally binding agreements between foreign investors and the US government, used to mitigate national security risks identified during CFIUS reviews. They often include specific requirements related to data security, technology transfer, and governance, and are monitored for compliance. Other CFIUS mitigation measures include divestitures, equity restrictions, and board observer rights.

- The International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) of 1977 grants the US President broad authority to regulate international commerce during declared national emergencies, including imposing sanctions and controlling transactions. It has been used to address various threats, from terrorism to foreign interference in elections.

Related articles

- 20Minds, Financial Regulation: A Stable Zone Amid Global Frictions?

- 20Minds, From Red Tape to Revenue: Unlocking the Strategic Power of Global Trade Compliance

- 20Minds, Global Trade and Investment

- 20Minds, AI and M&A

- 20Minds, AI Governance

- 20Minds, Horizon Scanner